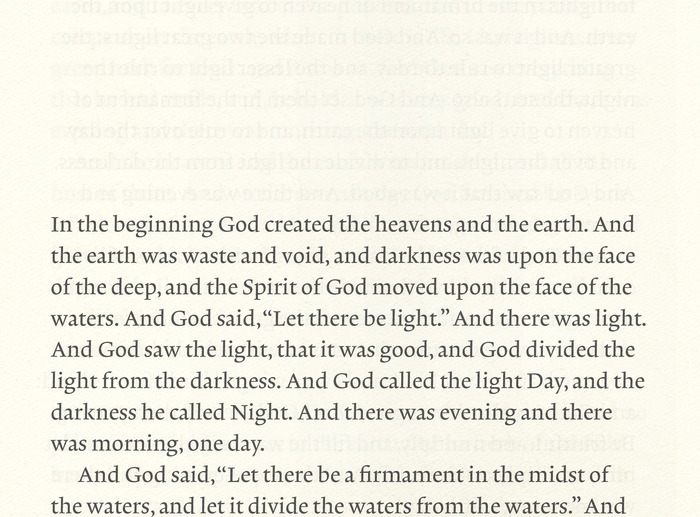

To escape from Bibles that are “ubiquitously dense, numerical, and encyclopedic in format,” an energetic venture is underway to create an “entire biblical library in four elegant volumes, designed purely for reading. The text is reverently treated in classic typographic style, free of all added conventions such as chapter numbers, verse numbers, section headers, cross references and notes.”

To escape from Bibles that are “ubiquitously dense, numerical, and encyclopedic in format,” an energetic venture is underway to create an “entire biblical library in four elegant volumes, designed purely for reading. The text is reverently treated in classic typographic style, free of all added conventions such as chapter numbers, verse numbers, section headers, cross references and notes.”

Bible Gateway interviewed Adam Lewis Greene (@AdamLewisGreene) about his ambitious Kickstarter project, Bibliotheca.

[UPDATE: The set is completed. Delivery is estimated to be December 2016.]

Briefly describe your Kickstarter project. Why do you think the donations exceeded your goal in almost an overnight timeframe?

Mr. Greene: Bibliotheca provides a fresh alternative to reading the biblical literature. It presents the text in four volumes, designed for an optimal reading experience. The best way to get a handle on the project is to watch the video, which was masterfully done by my good friends Daniel Williams and Joseph McMahon.

Though it’s hard to know exactly why Bibliotheca has been so well received, I think it has a lot to do with the fact that readers are ready to enjoy the Bible as the great literary anthology that it is, rather than as a text book. The idea of the Bible as story is moving and spreading rapidly. I have been deeply affected by this movement, and Bibliotheca is my attempt to create an elegant vehicle for it.

What need did you see that compelled you to conceive this project?

Mr. Greene: In my informal studies of biblical literature, I’ve been reading the likes of Robert Alter, N.T. Wright, and Kenneth Bailey, among others. Their work has changed the way I read the biblical literature by revealing its depth and value as literary art—as something intended by its authors to be read and enjoyed. (Two titles in particular are Alter’s The Art of Biblical Narrative and Wright’s The New Testament and the People of God.)

As a book designer, I began to conceive of ways I could translate these scholars’ abstract ideas into concrete aesthetic expression. So, the project itself and the overwhelming response to it are, I think, built largely upon the foundation of these scholars’ work as it seeps into our culture.

What does “Bibliotheca” mean and why did you select it as the project’s name?

Mr. Greene: Bibliotheca is Latin for library, or more literally, book case or space for books. Obviously that ties into the word “Bible.” For a long time the biblical library was referred to, in Latin, as Biblia Sacra, which means Holy Books. Somewhere along the line the plural form got lost in translation and became the singular “Holy Bible” in English (or “Holy Book”). When deciding on a name, it was important to me to convey that this literature is an anthology, made up of books, poems, and letters widely varied in style and authorship, and spanning thousands of years. Again, I’m breaking with convention here because the word “Bible” comes much later than the original documents, and frankly I think the singular form of the word can be misleading when separated from its history. I think for many people, the word “Bible” has come to mean “enormous religious book that I’ll never read.” Presenting the anthology under the title “Bibliotheca” is intended to jolt some of those preconceived notions.

Why are you keeping the set to four volumes and not another number?

Mr. Greene: The Hebrew Bible is divided into three volumes, based on the three traditional divisions of Tanakh, with one discrepancy: It seemed natural to include the Former Prophets within the same volume as The Five Books of Moses (rather than the more traditional combination of the Former and Latter Prophets) because of their stylistic similarity and narrative continuity. The remaining sections—the Latter Prophets and the Writings—make up the next two volumes. The Greek Christian Scriptures (The New Testament) are contained in one volume because they are naturally manageable in size and represent a relatively short span of literary time.

Why do you feel compelled to be so detailed in your production that you invented your own typeface and have specific reasons for page proportion and text block dimensions?

Mr. Greene: My approach goes back to ancient Hebrew scribal tradition, in which every aspect of the manuscript—the preparation of the animal hide, the number of lines on each page, the mixing of the ink, the type of script used, the space between letters—was carefully thought through, executed in reverence, and considered holy or “set apart.” While I haven’t exactly applied specific approaches from this tradition, I have long been inspired by the intention and reverence behind it, and have sought here to duplicate that in some way.

Design can function simply to make objects “look nice” on a very surface level, or it can become an integrated part of the object itself, adding meaning, depth and singularity to the experience.

Why did you decide to use the American Standard Version of 1901 as the project’s Bible translation and yet modify it? How do you respond to people who wish you would use a modern translation and those who would like the Apocrypha included?

Mr. Greene: The American Standard Version, like so many translations, is a double-edged sword.

On one hand, I love it; it is an exceptionally accurate translation (much more committed to formal literalism than any contemporary popular translation); it is not currently affiliated with any particular denomination or theology; and its English is beautiful, nuanced, and sophisticated (which, for me, adds to its literary quality).

On the other hand, some people don’t love it; it is criticized for being “too” formally accurate (and therefore difficult); is indeed not one of the many fashionable translations of our day; and its English is certainly not colloquial.

As a way to offset it’s strangeness to modern readers, I’m replacing the redundant archaisms with modern equivalents (“thou” will become “you”; “doth” will become “does”; “sitteth” will become “sits”; etc.). Also, in cases where the Elizabethan of the King James (of which the ASV is a revision) is clearly an issue for intelligibility, I will be very minimally adjusting syntax by the authority of Young’s Literal Translation of the Holy Bible; another excellent work of translation in its own right.

That said, this is still not going to read like The Hunger Games. It can be said that the English of the ASV is difficult, but it can also be said that the writings of William Shakespeare, Jane Austen, and Charles Dickens are difficult. And they are, but most of us agree that they are well worth our effort. I knew going into this that the ASV wouldn’t please everyone, but it is my favorite complete translation. I appreciate it’s conveyance of the “otherness” of the ancient languages, and I posit that it is one of the last great literary translations of the Bible into English (though I believe we are on our way to seeing more, with Robert Alter well on his way to completing his translations of the Hebrew Bible, and with David Bentley Hart working on the New Testament).

Regarding the exclusion of the Deuterocanonical books (or Apocrypha), I simply chose to use Jerome’s standard, by which the canon is made up of the Hebrew Scriptures and the Greek Christian Scriptures (The New Testament). This is not to say that I don’t think very highly of these writings (I do), and it has not been my intention to offend Catholic or Orthodox readers. In fact, I am currently looking into adding the Deuterocanonical books as a fifth volume; perhaps available to order separately after the campaign.

In our correspondence leading up to this interview, you said, “I believe a combination of sites like Bible Gateway and editions like Bibliotheca are the future of how people will experience the biblical literature.” Explain what you mean.

Mr. Greene: Digital study tools such as BibleGateway.com, BibleStudyTools.com, Lumina.Bible.org, and Logos Bible Software are far surpassing the capabilities of even the most dense study-oriented printed Bibles. Now, we have at our fingertips the power to dynamically study the Bible with customizable annotation from varied theological perspectives spanning the entire history of biblical exegesis. And we can easily read several translations in parallel and alongside original language sources.

No printed Bible can compete with the efficiency, economy, and portability of these study tools. We should gladly welcome these new forms, and I see it as an opportunity to re-evaluate the goals of printed Bibles. We can begin to ask ourselves, what strengths are there in printed books, and how can we start reincorporating these into the biblical literature? There are plenty of benefits to the sensory experience of a well-made book that digital mediums are as yet unable to provide.

One thing we have to keep in mind is that Bibliotheca is merely a new expression of very old ideas. The numerical-encyclopedic nature of our Bibles is completely foreign to how the literature was conceived by its authors and experienced by it’s first audiences. We have simply taken it out of its original garb and forced it into a Post-Enlightenment guise. There have been occasional reversions to more pure literary expressions of the Bible in the past several hundred years (two relatively recent examples are The Verona New Testament and the Nonsuch Bible), but they’ve always been outweighed and overrun by the encyclopedic status quo. Now, however, we might see the scales begin to tip in the other direction. I don’t imagine this will happen quickly, but times are changing.

What’s your opinion of The Saint John’s Bible, especially as a typographer/book designer yourself? Do you see Bibliotheca fitting in with that same artistic approach to Bible publishing?

Mr. Greene: I think the Saint John’s Bible is beautiful. It’s a very direct stylistic reversion to medieval manuscripts, and yet it brings a lot of surprising newness to the table. Though it is more niche and less “usable” than what I’m aiming for with Bibliotheca, that does not detract from its value in the least. As I’ve said elsewhere, there is a time to treat these texts extravagantly and the ways in which this can be done are endless. This brings The Golden Cockerel Press Four Gospels to mind, arguably one of the most important and beautiful books of the last century. These two examples offer extravagance primarily through a stunning and expressive visual experience; Bibliotheca is more concerned with offering extravagance through fluidity in reading and simple elegance.

There is plenty of room for creative expression when it comes to this literature—history is clear about that— and I think new forms will continue to surprise us.

Is there anything else you’d like to say?

Mr. Greene: I am very grateful for the incredible response to Bibliotheca. It is allowing for what I thought would be a relatively small project to scale much larger. Professional editing & proofreading, future print runs, and perhaps alternate translations (to suit the preferences of others), are now very likely. There has also been a lot of interest in making Bibliotheca available in other languages. I’m absolutely thrilled, too, that the response is not limited to one sort of reader. I’ve read many personal messages, tweets and posts from people of all kinds of backgrounds and beliefs who are excited to read the literature for the first time. For me, there is nothing that could validate the project more.

[An extended interview with Adam Lewis Greene is published on Bible Design Blog: Part 1 and Part 2.]

Bio: Adam Lewis Greene is a freelance designer and illustrator living and working in Santa Cruz, California. He’s been professionally involved in book design and illustration for five years.